A brand new booklet summarizes four years of psychological research on conspiracy theories and disinformation

During June 2025, our two large projects (APVV-20-0335 and APVV-20-0387) were completed. These projects focused on the psychological and social perspectives on epistemically unfounded beliefs, especially conspiracy theories and disinformation. They were conducted from 2021 and addressed the growing prevalence of unfounded beliefs and related negative phenomena during the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. The research provided important insights into the mechanisms underlying the origin and spread of unfounded beliefs, as well as how these beliefs are influenced by cognitive biases, negative emotions, and social conditions. One output of both projects is a freely available booklet summarizing these findings.

The first project („Psychological context of unfounded information and beliefs related to the COVID-19 pandemic“)

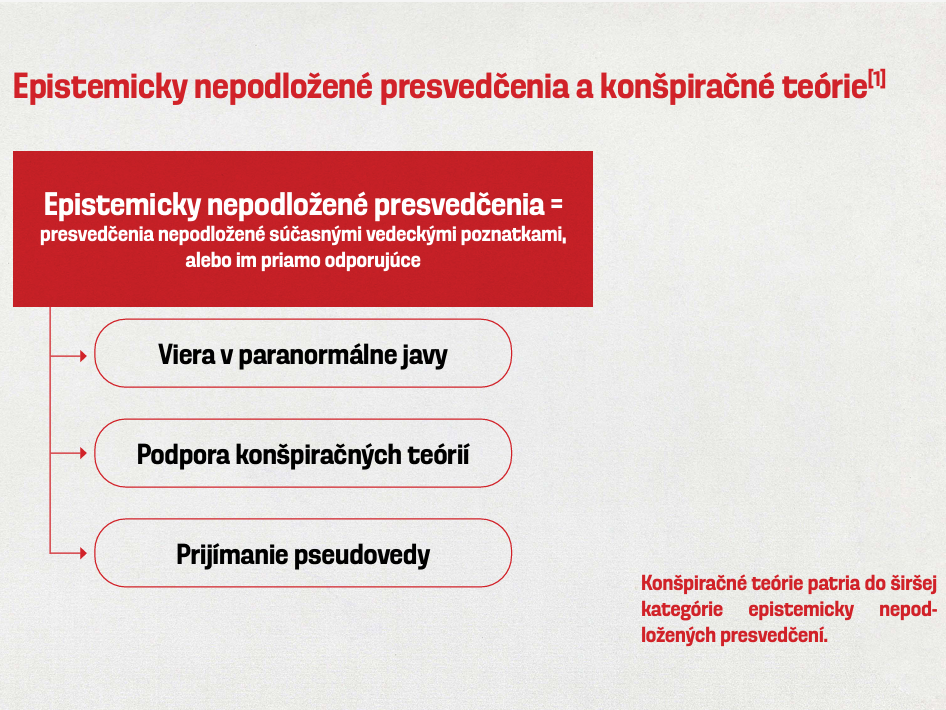

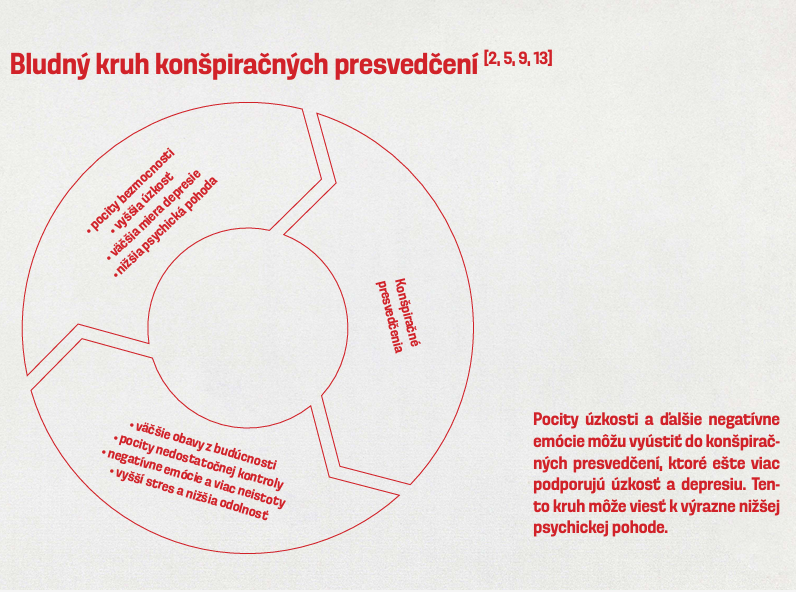

focused on the long-term psychological and social consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly on how the pandemic contributed to the spread of conspiracy beliefs, loss of institutional trust, and maladaptive behavior. Within this project, a three-wave longitudinal data collection was conducted, allowing us to track changes in unfounded beliefs over time and to determine the sequence of potential causes and consequences. One of the most significant contributions of this project concerns the identification of long-term negative social consequences of conspiracy theories. For instance, the findings show that individuals prone to conspiracy beliefs are less satisfied with their living standards, experience greater financial insecurity, and are more likely to expect future financial difficulties. At the same time, they are less willing to take steps to stabilize their financial situation. Feelings of helplessness and distress are associated with greater susceptibility to conspiracy theories and pseudoscientific beliefs.[1] However, the research also showed that conspiracy and pseudoscientific beliefs intensify these negative feelings over time, and that their effect on increasing helplessness and psychological distress is stronger than the effect in the opposite direction. Overall, this complex relationship is reciprocal, suggesting mutual reinforcement.

A similar bilateral relationship and mutual reinforcement between conspiracy beliefs and distrust in institutions and experts was demonstrated in another study [2]. An interesting finding is that while these relationships were reciprocal in the case of trust in government, a stronger negative effect of conspiracy beliefs was observed in declining trust in experts (researchers and doctors). These findings indicate that unfounded beliefs can weaken trust in key institutions, with serious consequences, especially during periods of health and social crises.

The project also focused on the long-term relationship between conspiracy beliefs and economic anxiety. A series of two studies [3] found that conspiracy beliefs across different cultural contexts are associated with increased economic anxiety. Longitudinal analyses confirmed that conspiracy beliefs increase feelings of economic anxiety, rather than the reverse.

The first project („Psychological context of unfounded information and beliefs related to the COVID-19 pandemic“)

focused on the long-term psychological and social consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly on how the pandemic contributed to the spread of conspiracy beliefs, loss of institutional trust, and maladaptive behavior. Within this project, a three-wave longitudinal data collection was conducted, allowing us to track changes in unfounded beliefs over time and to determine the sequence of potential causes and consequences. One of the most significant contributions of this project concerns the identification of long-term negative social consequences of conspiracy theories. For instance, the findings show that individuals prone to conspiracy beliefs are less satisfied with their living standards, experience greater financial insecurity, and are more likely to expect future financial difficulties. At the same time, they are less willing to take steps to stabilize their financial situation. Feelings of helplessness and distress are associated with greater susceptibility to conspiracy theories and pseudoscientific beliefs.[1] However, the research also showed that conspiracy and pseudoscientific beliefs intensify these negative feelings over time, and that their effect on increasing helplessness and psychological distress is stronger than the effect in the opposite direction. Overall, this complex relationship is reciprocal, suggesting mutual reinforcement.

A similar bilateral relationship and mutual reinforcement between conspiracy beliefs and distrust in institutions and experts was demonstrated in another study [2]. An interesting finding is that while these relationships were reciprocal in the case of trust in government, a stronger negative effect of conspiracy beliefs was observed in declining trust in experts (researchers and doctors). These findings indicate that unfounded beliefs can weaken trust in key institutions, with serious consequences, especially during periods of health and social crises.

The project also focused on the long-term relationship between conspiracy beliefs and economic anxiety. A series of two studies [3] found that conspiracy beliefs across different cultural contexts are associated with increased economic anxiety. Longitudinal analyses confirmed that conspiracy beliefs increase feelings of economic anxiety, rather than the reverse.

The second project ("Reducing the spread of disinformation, pseudoscience and bullshit") focused on cognitive aspects, personality traits, and social factors that contribute to the acceptance and spread of disinformation and unfounded beliefs. The effectiveness of various strategies against disinformation was also tested. Two studies [4; 5] demonstrated that anti-conspiracy arguments can reduce conspiracy beliefs and non-normative political behavior among individuals with deeply rooted views, although their impact remains limited in topics such as vaccination. These results suggest that debunking may have limited effects on long-held unfounded beliefs and that assessing the effectiveness of interventions in controversial topics requires further research.

The effectiveness of corrective messages containing factual information was also examined [6], and the impact of the timing of corrective interventions was compared—before exposure to disinformation (prebunking) and after exposure (debunking). Debunking significantly reduced trust in misleading claims, and these effects persisted for several weeks. Prebunking was effective only for a very short period or when applied shortly before exposure to disinformation.

The results of both projects provide new insights into the vicious cycle of conspiracy beliefs, distrust, and emotional distress, highlighting the combined role of cognitive biases, negative emotions (such as anxiety and helplessness), and broader social factors, such as economic precarity and political polarization. These findings have not only theoretical significance but also practical value, offering recommendations for effectively limiting the spread of disinformation and increasing societal resilience through targeted communication and education.

The effectiveness of corrective messages containing factual information was also examined [6], and the impact of the timing of corrective interventions was compared—before exposure to disinformation (prebunking) and after exposure (debunking). Debunking significantly reduced trust in misleading claims, and these effects persisted for several weeks. Prebunking was effective only for a very short period or when applied shortly before exposure to disinformation.

The results of both projects provide new insights into the vicious cycle of conspiracy beliefs, distrust, and emotional distress, highlighting the combined role of cognitive biases, negative emotions (such as anxiety and helplessness), and broader social factors, such as economic precarity and political polarization. These findings have not only theoretical significance but also practical value, offering recommendations for effectively limiting the spread of disinformation and increasing societal resilience through targeted communication and education.

The research identified the following practical recommendations applicable to everyday life:

• Be cautious of excessive confidence in your own judgments. Our research showed that most people believe they can distinguish truth from falsehood, yet they often make mistakes. Those who overestimate their abilities are the most vulnerable to disinformation.• Improve media literacy. We demonstrated that even simple tips can enhance the ability to detect false news.

• When encountering disinformation, factual correction (debunking) has a greater effect on reducing trust in disinformation than preventive correction.

• Consider that economic insecurity and low institutional trust increase susceptibility to conspiracy beliefs. Strengthening institutional trust and improving economic conditions may help reduce the spread of such beliefs.

• Do not ignore feelings of anxiety and helplessness, as these can increase vulnerability to disinformation. Building psychological resilience and improving stress management are important forms of prevention.

A brief summary of key findings and recommendations from both projects can be found in an informational booklet available for download.

Resources:

[1] Ballová Mikušková, E., & Teličák, P. (2024). Unfounded beliefs, distress and powerlessness: A three‐wave longitudinal study. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 16(4), 1539-1564.

[2] Merva, R., Šrol, J., & Čavojová, V. (2025). Institutional Distrust: Catalyst or Consequence of the Spread of Unfounded COVID-19 Beliefs?. Studia Psychologica, 67(1), 24-37

[3] Adamus, M., Chayinska, M., Šrol, J., Adam‐Troian, J., Ballová Mikušková, E., & Teličak, P. (2025). All you'll feel is doom and gloom: Multiple perspectives on the associations between economic anxiety and conspiracy beliefs. Political Psychology.

[4] Šrol, J., Čavojová, V., & Adamus, M. (2025). Dispelling the fog of conspiracy: Experimental manipulations, individual difference factors and the tendency to endorse conspiracy explanations. Thinking & Reasoning, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2025.2464962

[5] Adamus, M., Ballová Mikušková, E., & Kohut, M. (2024). Conspire to one's own detriment: Strengthening HPV Program Support Through Debunking Epistemically Suspect Beliefs. Applied psychology. Health and well-being, 16(4), 1886–1904.

[6] Lorko, M., Čavojová, V., Šrol, J., Priesol, R., Jalakšová, P., & Tužilová, B. (n.d.). Timing matters: Three-study test of the effects of debunking vs. prebunking on trust in disinformation.

Views: 1